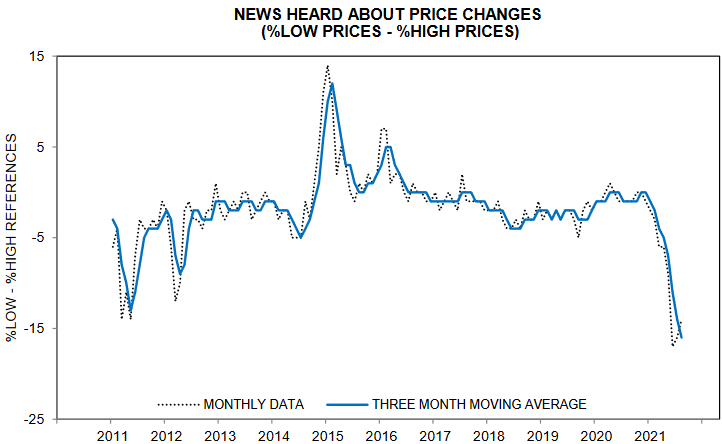

Recent consumer sentiment surveys reveal that Americans have clearly started to notice rising prices for goods and services. Goods inflation has by far been the biggest driver of 2021’s price gains, and according to some estimates this has already cost U.S. consumers $87 billion this year.

As large as that might sound it is dwarfed by the $2.2 trillion excess savings buffer Americans built up since the pandemic started through a combination of increased savings rates and trillions in government stimulus. This helps explain why reports on consumer spending have for the most part generally exceeded estimates all year. Of course the savings glut is not infinite, and continued price increases could indeed eventually start to materially drag on consumption.

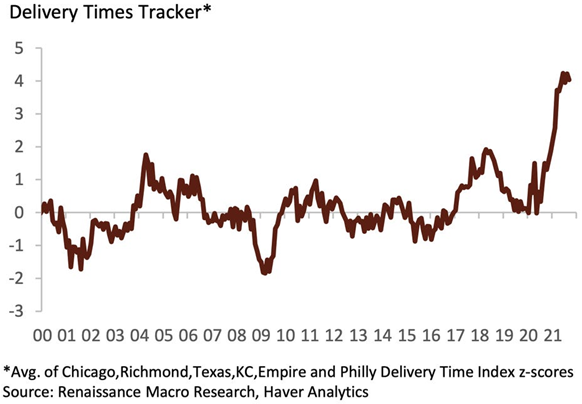

However, a reason to remain optimistic is that recent goods inflation has largely resulted from global supply logjams (brought about by the pandemic and exacerbated by elevated consumer demand for goods), and incoming data encouragingly suggest that we may finally be at or even past peak supply chain shortages. For example, the latest business activity report from the Institute for Supply Management showed that in September general inventory sentiment improved even as total supplier deliveries declined, together implying that although shortages persist they have become less of an impediment for some firms. Similarly, there are signs that global shipping rates may be leveling off, and there is also evidence that the surge in vendor delivery times has stalled.

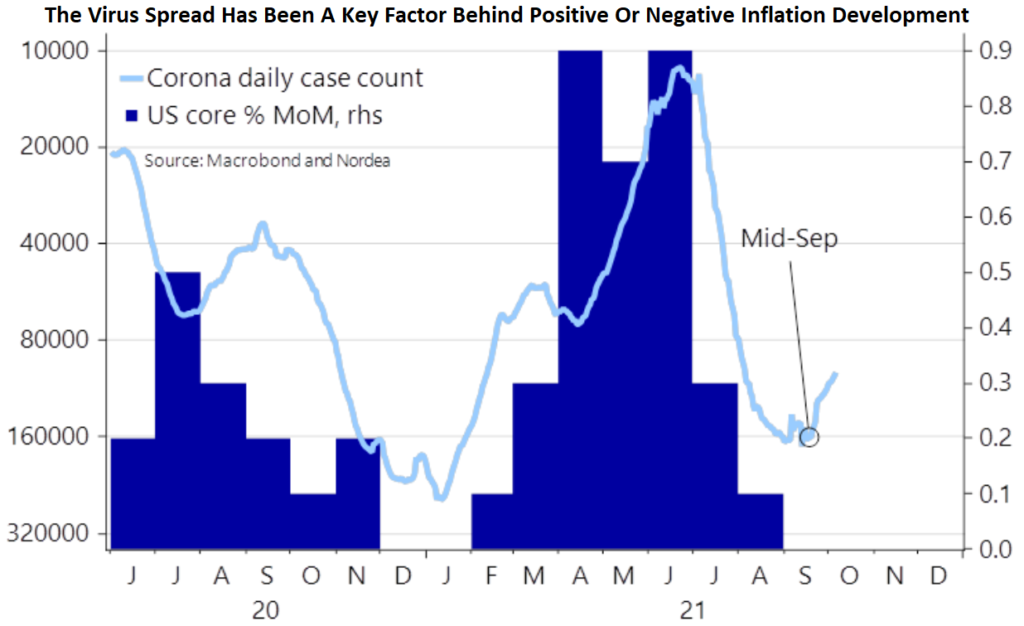

To be fair such measures are still extremely elevated and supportive of further price increases, but “not getting any worse” is an important first step toward “starting to decline.” Additional help will come from increased factory activity as COVID cases continue to decline and enable greater capacity utilization (both domestic and abroad), and encouragingly a report from ADP revealed that manufacturing hiring is already starting to ramp up again. Moreover, the ebbs and flows in manufacturing payrolls line up well with COVID case counts (inverted), which further supports our earlier argument that many of the recent inflation challenges are closely tied to transitory side-effects of the pandemic that should fade along with the virus.

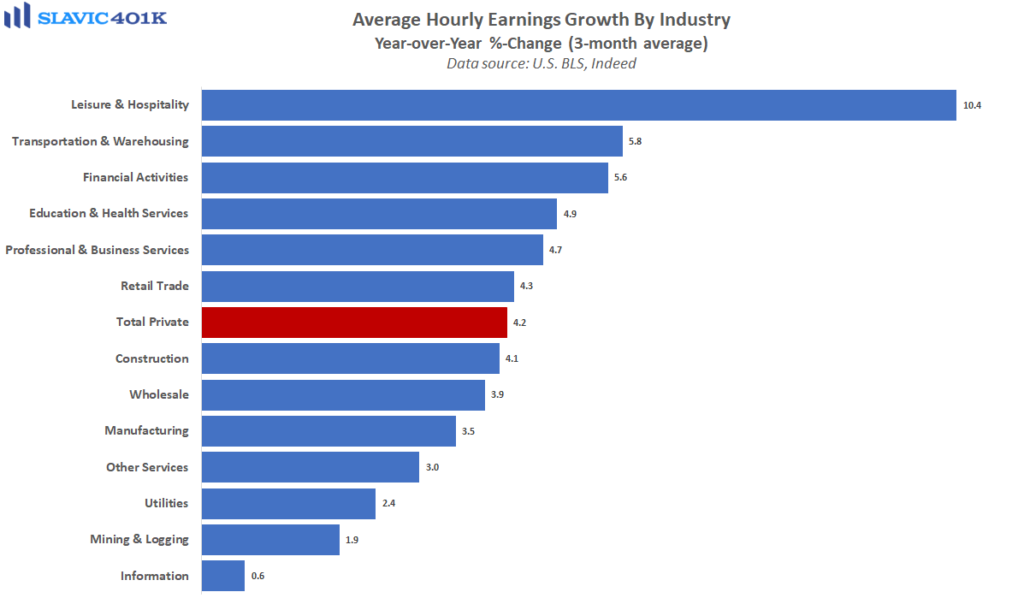

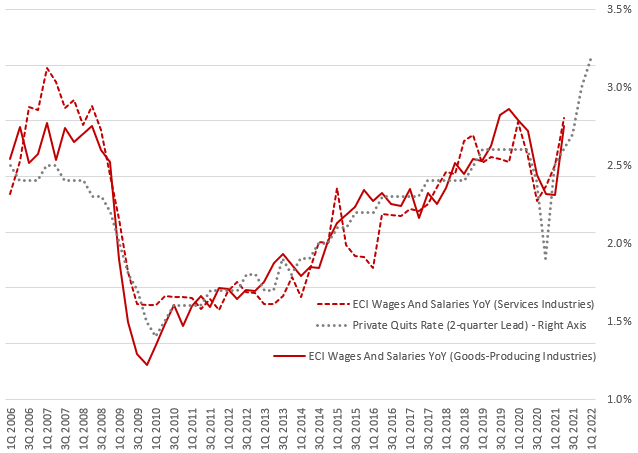

Of course goods inflation is only one part of the equation, and as we have argued before a more lasting inflation risk could come from employment costs. Indeed, in September average hourly earnings grew by 0.6 percent, topping expectations but the beat was due mainly to the prior month’s gain being revised downward. However, average hourly earnings still increased by 4.6 percent compared to this same period last year, well above the typical 3.3 percent pre-COVID pace. Strong labor demand alongside an inadequate supply of jobseekers will always put some kind of upward pressure on wages, so the growth rates we are seeing in compensation should not be surprising given some of the recent economic data releases.

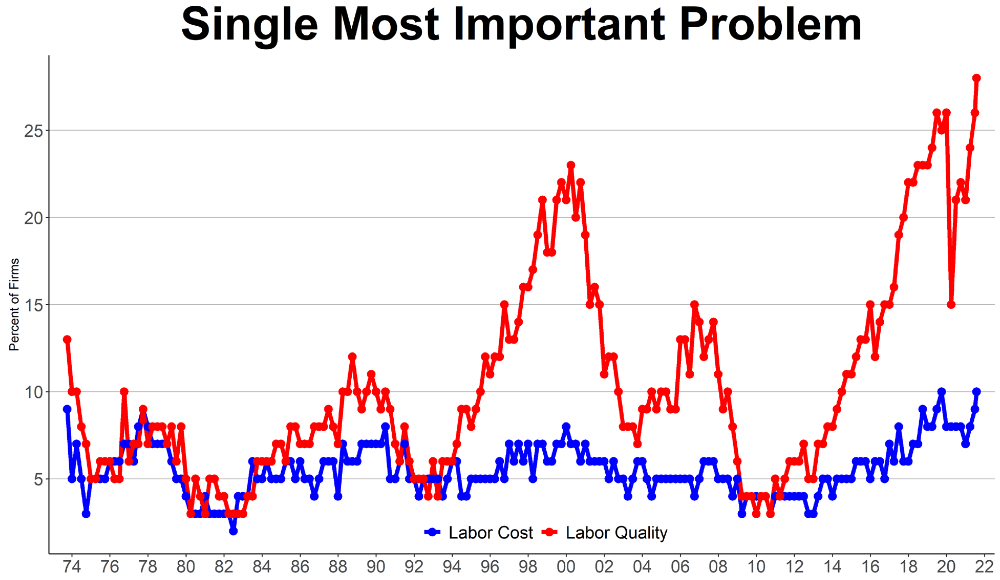

In the latest NFIB small business owners survey, for instance, a record 51 percent of respondents reported having job openings they could not fill, and 62 percent reported “few or no” qualified applicants for the positions they were trying to fill. Some industries are experiencing even greater labor shortages at the moment, such as the construction sector, where a whopping 80 percent of small business owners last month reported few or no qualified applicants. Moreover, a net 42 percent of surveyed owners reported raising compensation recently, a 48-year high, and a record 12 percent cited labor costs as their top business problem currently, not surprising since for most firms labor costs are the largest operating outlay.

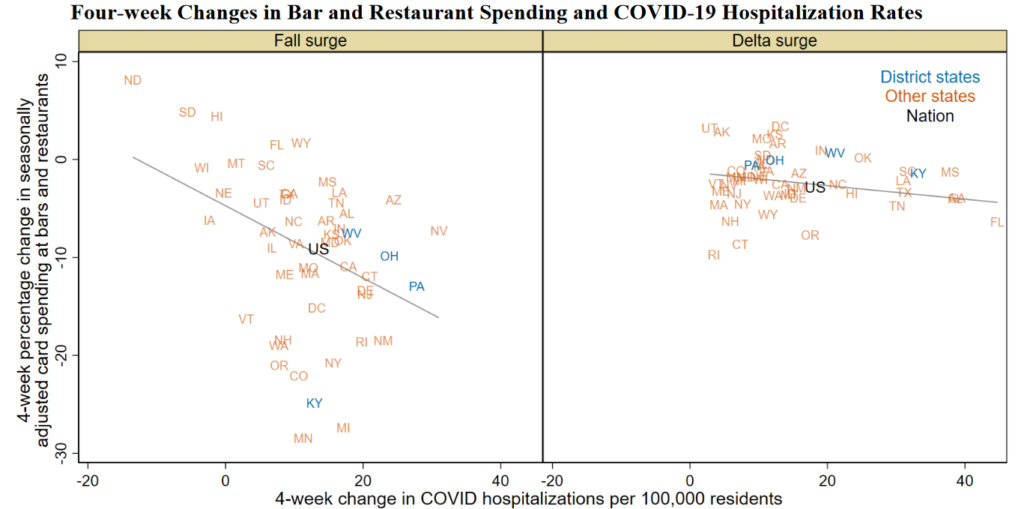

It is also worth noting that small business owners’ complaints about poor sales fell in September to a multi-decade low, implying firms still have substantial pricing power, which could further influence wages going forward. More generally, though, the good news is that sector-level data continue to suggest the bulk of the supply and demand imbalance in the labor market remains tied directly or indirectly to the pandemic, and therefore such hindrances should abate as COVID cases continue to decline. Things are of course complicated by the rise of new variants and infection waves, but these rolling disruptions so far appear to be having a diminishing impact on economic activity, e.g. metrics such as air travel and restaurant foot traffic have experienced shallower declines and swifter recoveries with each subsequent wave of the pandemic.

Another positive is the full expiration of the federal unemployment benefit. This work disincentive finally ended in early September but any resulting boost to payrolls growth could be a more gradual process (take time to show up), i.e. stronger household balance sheets mean more time needed for savings to be sufficiently drawdown and result in an uptick in jobseekers. Regardless, a lot of conditions appear to be falling in place to potentially make for a strong year-end hiring push. As we have repeatedly argued, though, real clarity on the labor market recovery and future trajectory of wages will likely not be available until 2022 after the bulk of the COVID-related base effects and extreme seasonal adjustments are behind us.

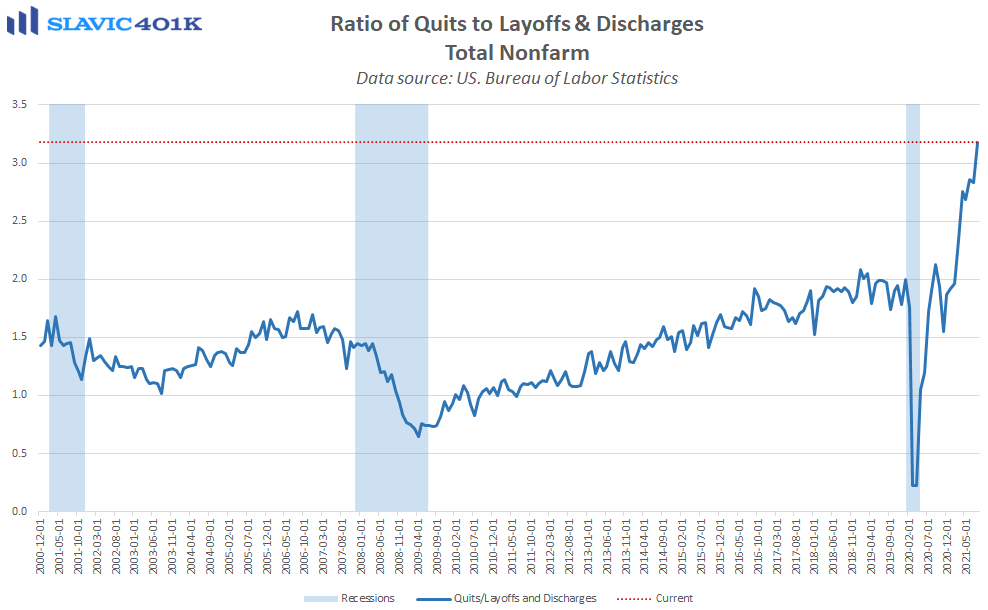

As for what we will want to watch next year to know if wage growth is really going to drive sustained consumer price increases, we will need to see evidence of continued, above-trend gains in compensation, and historically this only really occurs when worker bargaining power is very high, i.e. employees’ ability to pressure employers for greater compensation. Although there is no single indicator to track, useful metrics we can monitor that are highly correlated with worker bargaining power include the unemployment rate and union trends.

With respect to joblessness, unemployment rates across the country have fallen a lot from the crisis peak but in general have yet to return to pre-COVID lows. As for unions, gauges of membership and strike days per year, albeit elevated, have yet to reach and hold levels historically consistent with inflationary potential arising from the labor market. None of this means worker bargaining power cannot continue to firm going forward, or that general consumer prices will not keep drifting higher, but for now the data still do not support the recent deluge of warnings about a long-term, out of control price spiral.

What To Watch This Week:

Monday

- Industrial Production 9:15 AM ET

- Housing Market Index 10:00 AM ET

Tuesday

- Mary Daly Speaks 8:00 AM ET

- Housing Starts and Permits 8:30 AM ET

- Patrick Harker Speaks 8:50 AM ET

- Raphael Bostic Speaks 1:00 PM ET

- Raphael Bostic Speaks 2:50 PM ET

Wednesday

- MBA Mortgage Applications 7:00 AM ET

- EIA Petroleum Status Report 10:30 AM ET

- Raphael Bostic Speaks 12:00 PM ET

- Charles Evans Speaks 12:00 PM ET

- 20-Yr Bond Auction 1:00 PM ET

- James Bullard Speaks 1:45 PM ET

- Beige Book 2:00 PM ET

- Mary Daly Speaks 8:35 PM ET

Thursday

- Jobless Claims 8:30 AM ET

- Philadelphia Fed Manufacturing Index 8:30 AM ET

- Existing Home Sales 10:00 AM ET

- Leading Indicators 10:00 AM ET

- EIA Natural Gas Report 10:30 AM ET

- 2-Yr Note Announcement 11:00 AM ET

- 5-Yr Note Announcement 11:00 AM ET

- 7-Yr Note Announcement 11:00 AM ET

- 5-Yr TIPS Auction 1:00 PM ET

Friday

- PMI Composite Flash 9:45 AM ET

- Mary Daly Speaks 10:00 AM ET

- Baker Hughes Rig Count 1:00 PM ET